Taking on the 56-kilometer hike around Gang Rinpoche is not a feat for the faint of heart, but both the physical and mental challenges are outweighed by the exhilarating experience and spectacular views, Xing Wen reports in Ngari, Tibet.

Climbing a mountain is a fake challenge. At least, that's how Fran Lebowitz, the American writer and critic sees it, making the claim in the highly-rated documentary Pretend It's a City, in which she depicts the vicissitudes of contemporary urban life-its fads, trends, crazes and fashions.

Lebowitz says she finds that, nowadays, many people participate in activities such as mountaineering because they want to challenge themselves.

"A challenge is something you have to do, not something you make up," says Lebowitz. "You don't have to climb a mountain. ... I find real life challenging enough."

Her views make perfect sense to me. Even so, I was still itching to have a go when my friend, Zhang Tianyao, asked me if I want to take up the challenge to finish the grueling 56-kilometer trek that circles the Mount Kailash, or Gang Rinpoche in Ngari prefecture, Southwest China's Tibet autonomous region.

At the time, we were discussing how we should spend our annual leave.

"Do you want to try something exhilarating over the vacation? What about hiking around Gang Rinpoche?" he asked.

His words reminded me of a film I watched several years ago. The film, Path of the Soul, traces the pilgrimage of 11 Tibetan villagers from Chamdo to Gang Rinpoche, a mountain that holds a holy position in many religions, including Tibetan Buddhism and Hinduism. The pilgrims would prostrate themselves every few steps after setting off on the 2,500-km-long journey. I was impressed by their natural simplicity, kindness, endurance and perseverance.

At that time, for me, a person who had never ever set foot in Tibet, the mountain located in the remote western hinterland of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau seemed to be a faraway place beyond my reach.

However, Zhang proposed the endeavor in such a relaxed manner, it made me feel that the route would be something we could easily reach and conquer.

I had been feeling quite down and restless for some time. I assumed, perhaps a little naively, that maybe an epic mountain adventure would be just the tonic for my agitated state of mind and provide some inner peace.

"OK!" I replied assertively, steeled with a newfound determination.

With that, planning the trip began in earnest.

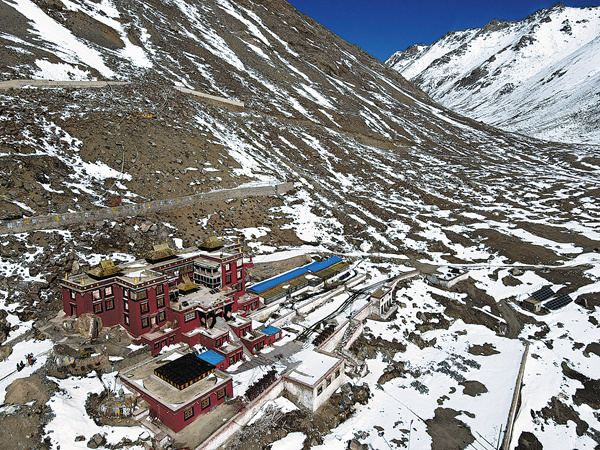

The Ngari prefecture, averaging over 4,500 meters above sea level, has a long, cold winter. Some parts of the prefecture, including Mount Gang Rinpoche and its nearby areas, were hit by a blizzard before our arrival in late October. Hiking and climbing at high altitude are already difficult, let alone when the paths are frozen or heavily carpeted in snow.

Our fitness and stamina would be put to the test, as we were certainly going to face freezing conditions, a lack of oxygen and extended exposure to the sun, as well as the specters of possible altitude sickness and exhaustion, among a litany of other dangers, both conceivable and inconceivable.

With this in mind, I carefully prepared my personal equipment, which included a pair of hiking poles, a down-filled jacket, a hooded fleece, knitted hats, woolen gloves and socks, climbing boots, sunglasses and an outdoor headlamp.

I packed all my gear and boarded a plane to Lhasa, capital of Tibet, where I met Zhang.

We still had to drive more than 1,200 km from Lhasa to Darchen, a small town located to the south of Gang Rinpoche. It's the starting point of many pilgrims who come to trek around the holy mountain.

Such a long journey was undoubtedly tiring, but there's no doubt that the specular views-featuring snowcapped peaks that seem to spear the clouds, lakes with mirror-like surfaces, brooks flowing through desolate landscapes and sand dunes sculpted by the wind, as well as herds of yaks and sheep alongside teams of horses roaming freely-were a feast for the eyes.

Getting closer to Darchen, we caught sight of a peak which, like a majestic snowy pyramid, towered above many of the other mountains. We immediately recognized the iconic natural wonder. That's Gang Rinpoche. At 6,658 meters, it is the second highest peak in the Gangdise Mountains.

During peak tourism season, a continuous stream of visitors arrives in Darchen to set off on their spiritual hike. Hotels and guesthouses can be seen everywhere in the small town, and the demand for rooms can often exceed supply at certain periods.

However, few tourists from other parts of China would choose to hike around the mountain in winter and, as such, it was much more convenient for us to book rooms in Darchen.

There, I met a 25-year-old Tibetan man who is a graduate from the China University of Petroleum in Beijing and lives in Lhasa. He told me that his family is driving across Tibet to visit all of the famous monasteries and holy sites for Tibetan Buddhists, and that finishing with the pilgrimage around Gang Rinpoche is on their to-do list.

"We set out at 3 am yesterday and completed the circle at 7:30 pm," he said.

"That's impressive!" I exclaimed, more than a little amazed, considering it is almost non-stop physical activity for 16.5 hours on a route that ranges in altitude from 4,600 meters to nearly 5,650 meters and spans a length that's just short of a marathon-and-a-half.

I couldn't help myself from sizing up the robust, suntanned man to estimate the gap in physical fitness between us.

"Generally, many local people are able to finish the journey within one day. Tourists normally choose to trek around the mountain for two days," he suggested.

We, wisely, took his advice.

Our plan was to begin the trek from Darchen in the morning and try to arrive at the staging post, located at an altitude of 5,370 meters where we would spend the night.

After a good sleep, I would wake up fresh, and with enough energy to slog up to the Domla La Pass, the highest and most difficult part of the route, on the second day, I assumed, once again, somewhat naively.

The first 20 km of the trail, which stayed under 5,000 meters altitude, was relatively easy going.

We were walking along the snow-covered path, talking, laughing and taking photos, though still paying close attention to the slippery frozen sections.

Sometimes, when we would stop talking, it would be so quiet that I could hear the snow squeaking under the soles of my boots. The holes in the thick snow banks alongside the path, made by hiking poles, are ubiquitous, appearing different shades of blue.

From time to time, we met Tibetan pilgrims who, clad in their traditional garments, were walking the trail in twos and threes. They would greet us with tashi delek (good luck in the Tibetan language) and a friendly smile.

We also saw some pilgrims, usually wearing aprons, who would fall down to the snowy, gravelled path every few steps while chanting sutras. Witnessing the pious ritual being carried out in such a harsh environment would remind me of the sacred position Gang Rinpoche holds in the hearts of the pilgrims.

Ascending to the sections above the 5,000-meter mark, I started to huff and puff, needing to take a short rest every few minutes. I was suffering from a lack of oxygen.

"No rush," Zhang would say.

"OK," I would breathlessly reply.

It was apparent that both of us had become less talkative than we were at lower altitude.

Fortunately, we managed to reach the staging post before sunset and found out that the beds we were going to pay 150 yuan ($24) each for were actually just long benches set out in rows inside a stone house. Given the harsh environment, the bedding on offer probably didn't get washed frequently, so it was perhaps not surprising that there was an unpleasant, mildewy smell about them.

The only heating facility was an old furnace that the house's owners used to boil water contained in a caldron.

They usually melt snow for drinking water.

We soon realized that we were the only two Han people staying in the house, and the Tibetan trekkers would occasionally come to chat with us in a pleasant, approachable manner.

Although the accommodation was not as comfortable as I had hoped, I felt a sense of excitement about gaining a special life experience.

My excitement, however, didn't last long. As night fell, loud snoring arose all around, filling the room.

I had a thoroughly anxious, sleepless night.

The next day, I forced myself to gather my strength for the final 29 km. We set off at around 9 am.

With the sun shining brightly on the snow-clad summit of Gang Rinpoche, the peak seemed to turn a radiant, golden yellow. Against the backdrop of a clear, blue sky, the holy mountain looked solemn and respectful.

The splendid morning view suddenly filled me with a strong sense of awe.

As we headed up a steep climb to the Domla La Pass, the wind howled and it started to get bitterly cold.

By that point, I had to stop every few steps to greedily gulp in lungfuls of the cold, thin air.

I was haunted by a headache and tiredness, and my fingertips had taken on a bluish tint.

I found, Zhang, however, was hiking much faster than me. Obviously, his body had already adjusted to the high elevation.

The rucksack on my back seemed to grow heavier with every trudging step as I clambered up the steep slope.

At that instant, a passing Tibetan woman noticed the difficulty I was facing.

"Are you OK? Shall I carry the rucksack for you?" she asked me.

The young pilgrim looked fit and wiry. I gratefully accepted her offer of help.

"I'll leave it at the Domla La Pass," she said and then climbed up the snowy incline with vigorous strides as if it were nothing.

"What a cool woman," I thought.

After that, I started to feel much more relaxed.

When we finally reached the Domla La Pass, at an altitude of 5,630 meters, a Lama came to hand me some snacks and said: "Congratulations!"

We also shared chocolate bars with the locals as a way of celebrating our collective achievement.

The trail back down was long and treacherously slippery. However, with no more mountain sickness, I could handle it.

In the end, though, it turned out that the mountain adventure, while epic in scale, was not enough to cure my negative feelings. I would still feel down or get annoyed over trifling matters.

Yet, I often recall the gorgeous sunset we were fortunate to experience while mechanically trudging through the sun-drenched snowfield for several hours.

As the sun fell behind the snowcapped mountains in the distance, the sky was ablaze with ever-changing colors including pink, blue, purple and orange.

The dazzling descending sun shone down upon the pilgrims who were dwarfed by the grand mountains as they silently walked along the trail.

The indescribably beautiful scene made me forget, albeit for a brief while, all the pain I suffered during the trek.

An immense gratitude for nature and for my own life arose inside me. At least at that moment, I got so close to my inner peace.

What else have I gained from the trek around Gang Rinpoche? Seriously, the sunburn left me with a dark mark on my nose. I don't know when it will disappear completely.

"Take it easy. The mark is a medal Gang Rinpoche presented to you," Zhang joked.

"OK," I acquiesce, less breathlessly this time.